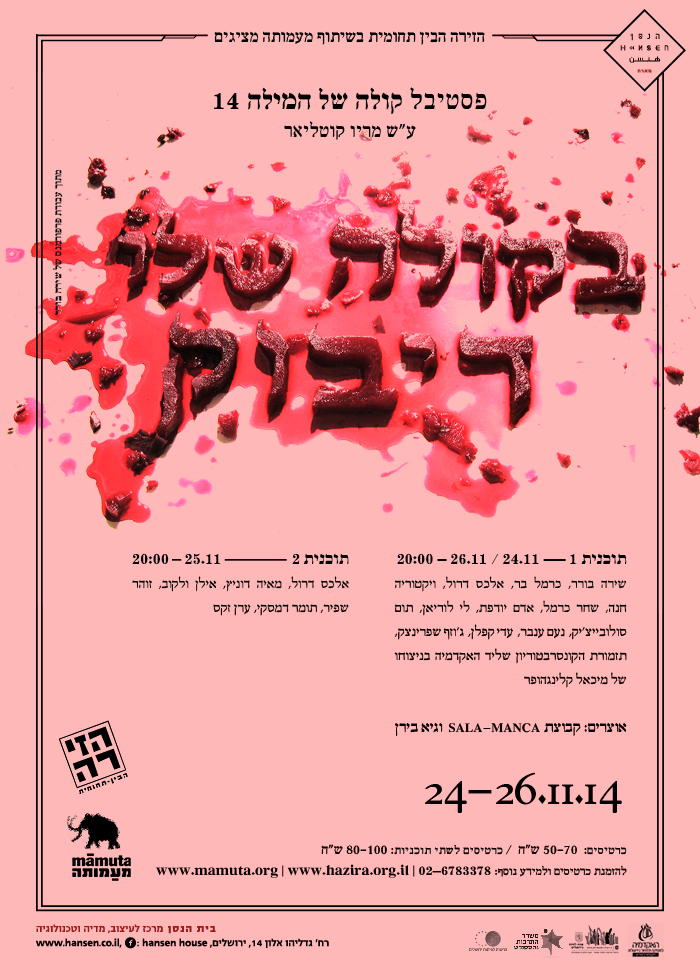

The Voice of the Word 14 – Performance and Music Festival, 2014

|

Participating Artists: Adi Kaplan, Shachar Carmel, Tom Soloveichik, Alex Drool, Josef Sprinzak, Carmel Bar, Li Lorian, Adam Yodfat, Victoria Hanna, Noam Inbar, Shira Borer, Jerusalem Conservatory Chamber Orchestra with Conductor Michael Klinghoffer, Ilan Volkov, Zohar Shafir, Tomer Damsky, Eran Sachs, Maya Dunitz

Curators: The Sala-Manca Group and Guy Biran The 14 Kola Shel Ha’Mila Festival Named after Mario Kotliar Bekola Shelo Dybbuk The Hazira Performance Art Arena’s flagship festival, now in its 14th year, examines the relationship between word/text and performance art. This year, the festival is being held in participation with the ‘Mamuta’ Center for Art and Media at Hansen House. in the photo: Joseph Shprinzak The dybbuk (an evil spirit in Jewish folklore) phenomenon, through Ansky’s play, is the basis and inspiration for this year’s Kola Shel Ha’Mila festival (The Voice of the Word). The Mamuta spaces at Hansen House, formerly a leper colony, are transformed into an area for challenging one’s spiritual transformation, as a metaphor for the ancient building’s newly designated mission. In Kola Shelo, Hansen House is granted the suppressed forces of experience, which connect past and present, art and ritualism, healing and performance. The dybbuk is an external force that penetrates the human body and causes it to behave erratically. According to tradition, the dybbuk is the spirit of a deceased person, which takes over a live body and speaks through it in another voice. The dybbuk is a way of coping with harsh social situations, voice dissent, for which the afflicted have no words, and reveal dark occurrences from a community’s past.

Maybe it’s because the Leper Hospital was previously known as “Jesus Hilfe”, or,”Jesus Help Asylum”, and it reminds us of two of Jesus’ qualities – healing and banishing demons; maybe it’s because in 1950 a different, political and ideological spirit possessed the building, and it was decided to change the hospital’s persona and rename it after Dr. Hansen, who discovered Leprosy’s origin and seemed, to the building’s new owners (Israel’s Health Ministry) , like the right spirit for the public body they now represented; maybe it’s because the Leper Hospital lost its function, became an arts and technology center, and was named “Hansen House”, as if it is the home of the spirit that replaced Jesus; maybe it’s because today, instead of the lepers, artists and students are the ones who live in the building, and sometimes challenge the local cultural hegemony; maybe it’s because one hundred years have passed since S. An-sky’s ethnographic expedition, where he collected a part of the stories that functioned as the play’s basis, and a hundred years since the play’s first drafts were written in Russian and Yiddish; maybe it’s because of all these things, separately or together, that we decided, as a part of the “The Voice of the Word 14″ festival, to return to one of the most profound traditions in Jewish culture, to dwell on an external spirit which possesses the body of a flesh and blood human being: the Dybbuk.

“Into the body of a living human being, with an individual, distinct soul, enters at a certain point in his life another soul – the soul of a person who died prematurely and was seen as a sinner so terrible, even entering hell was deprived from him, and he remains between two worlds, haunted and tortured by angels of destruction […] the Dybbuk seeks a refuge from its persecutors and enters the living body against its will, seizing it, sticking to it, possessing it and speaking from the mouth of the person possessed as a distinct personality” (Rachel Elior). Yoram Bilu writes that the urges and aspirations that stand at the base of this disorder were challenges that threatened the traditional Jewish lifestyle. The play was written during the years 1912-1917 in Russian and Yiddish, and was inspired by the traditions and stories of the Dybbuk that An-sky collected when he was the head of an ethnographical expedition to Volhynia and Podolia. The play was performed many times by different groups, and through the years became a canonical play in Jewish theater’s history, in Yiddish and in Hebrew.

“The Voice of the Word” festival deals with the connection between the text and its performative aspects. In “His Voice in Her: Dybbuk” we suggested a refraction of the play using its motives, texts, or characters. Each of the parts the artists chose takes place in the historical building the architect Conrad Schick designed. The play, whose acts develop on a timeline, develops in the festival with its dispersal throughout the different spaces: Time becomes territory.

Divorce ceremonies, interpretations using auditory activities and works, mechanical theater, mixes of sounds and images, archived material and live happenings, edits of old movies mixed with live performances of a youth orchestra – all these give one of the Jewish theater’s classic plays in Hebrew and in Yiddish a modern take. The artists once again bring up questions on ownership, on national and gender identity, on possession, on sound and spirit and on the spirit of time and convey a feeling that must be similar to the one created during the play’s performances in the 1920’s: The feeling that one world of values is disappearing, and a new one is taking its place.

|